E21. The Second Dream of Lou Reed’s Nephew’s Narrator

I find myself mouthing Bob Dylan, who I’ve always hated.

Ulugbek and I sit close together, like astronauts.

“Back-to-back,” I say. “Isn’t it funny?”

“What’s so funny?” he says. “Like Soyuz.”

“Soy-what?”

“Union,” he says. “U.S./Soviet joint mission.”

We get to Lafayette Street and point our hovercraft north. Ulugbek keeps a lookout, manning the brushes and making sure we don’t hit anything.

“Put in ticket,” he says.

We glide up the valley of Lafayette Street. At Astor Place, the police arrive to clear out the square. They do this daily so we can AM the place. Once they’re gone, Ulugbek and I roll up in our craft and I tell him to fire up the AM engines. He doesn’t—he won’t—so I send him a ticket with my handheld.

It is clear as soon as he engages them that something has gone wrong. We have hit something, but it’s not a building. It’s something more momentous, a main of information beneath Astor Place. Now it is gushing. It erupts before us like a Mosaic pillar, a mushroom cloud thousands of miles high.

I somehow understand, the way one does in dreams, that this geyser contains everything electronic that had been previously hidden. All the places and events that Ulugbek and I have carefully ingested, and much more. After 612 days of going to bed thinking about data—the skeleton of the electronic world—my dreams are filled with relational tables, joined by key variables, extending forever. There is something beautiful about it, this daisy chain of information with infinite extensibility, optimized to the sixth normal form.

You have a single line in a table of all the places, representing just one place. The place has a unique identifier and another table, linked to the first by this identifier, contains all the events that happen at the place. Then another table, linked to the second by the unique identifier of the event, contains all the information about the event that remains the same, wherever it might take place, and so on. From these tables you can create new tables, remixing the information they contain. Once you know this, you see the world differently. You see through it, to the structure that transcends the homely zip codes and dates that appear in the individual lines.

It was this structure that expressed itself as a blinding Jacob’s ladder above the East Village in my dream. It contained all our emails, everything we’ve ever said about anyone, everything anyone’s ever said about us, the identities of all trolls, all the loosely autobiographical novels we had started in apps we no longer use. Not just for Ulugbek and me, but for every human being on Earth.

I am horrified. (And not just because it means the end of our database. This is bigger than that.) I find myself mouthing Bob Dylan, who I’ve always hated. “If my thought-dreams could be seen, they’d probably put my head in a guillotine.” Ulugbek completes the line as we lock eyes in our rearview mirrors. “It’s life, and life only.”

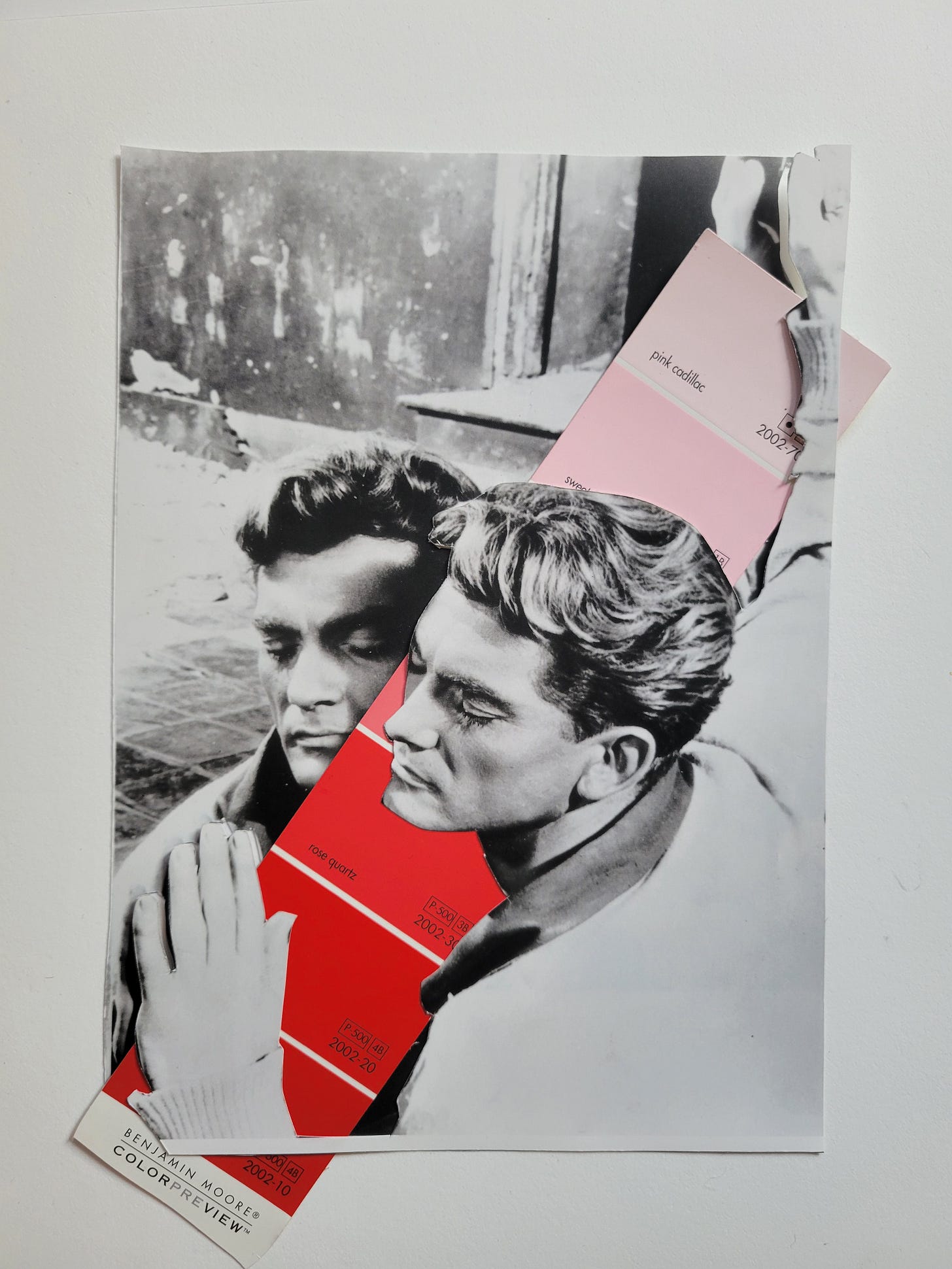

Suddenly Astor Place is flooded. Buildings drain themselves of their inhabitants. The sea of people stretches as far as I can see, up and down Lafayette and across eighth street in both directions. There will be a riot, I think. A mass of furious people stripped of their most treasured possessions—their secrets—with nothing left to lose. The streets will run red with privacy, to be followed by real blood.

But that is not what happens. The people aren’t furious. They are exhausted and relieved. They swoon into each other’s arms in a collective sigh and squint into the sun, as if for the first time, as they prepare to start over, with no secrets, no illusions.