E6. Beybi: Authority for Life

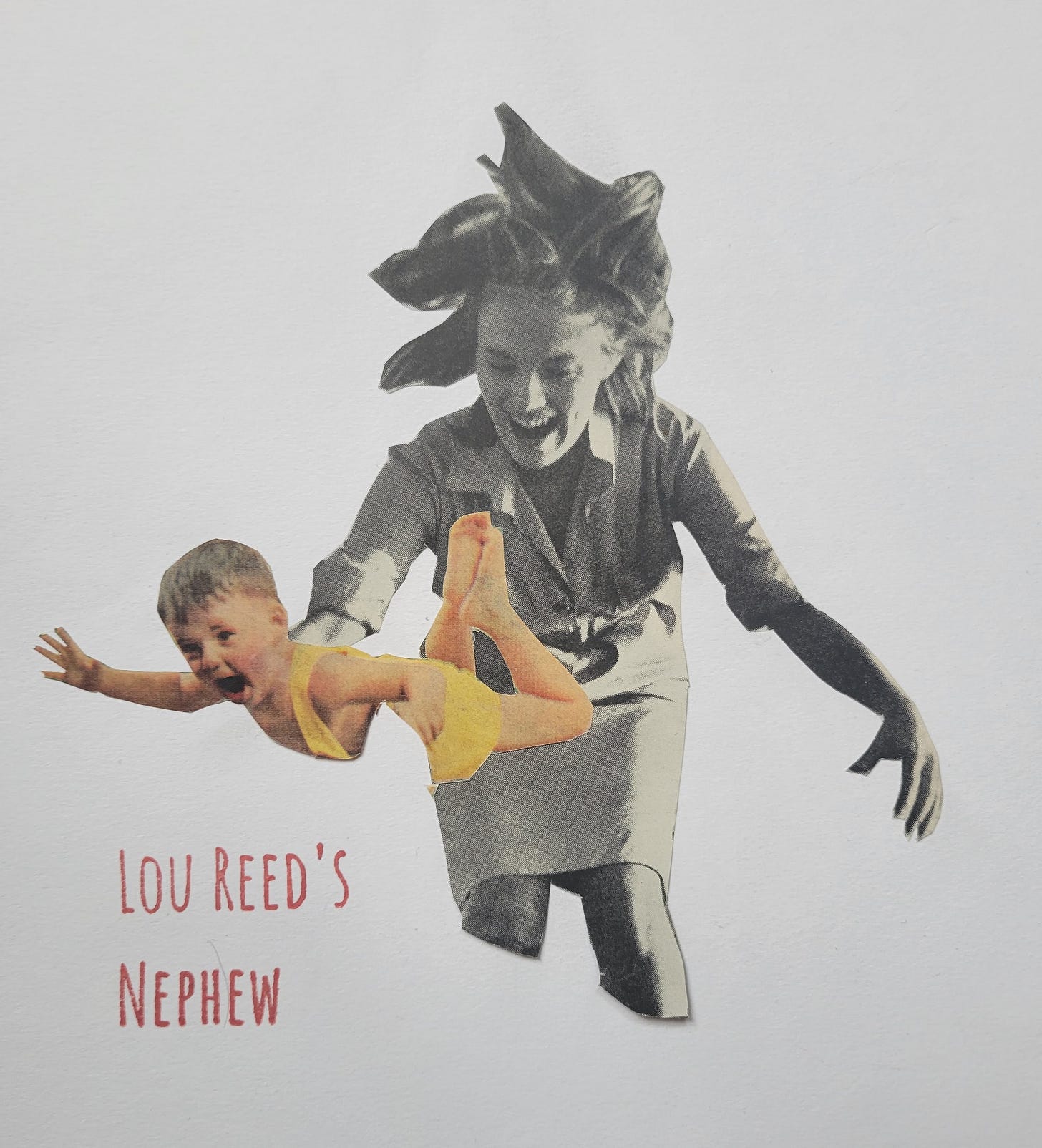

“Parents do love authority,” Lou Reed’s Nephew agreed.

On the first Tuesday of each month, Lou Reed’s Nephew took over one of the small conference rooms on our floor from ten o’clock to two o’clock. Our cubes entitled us to “two monthly clock hours of Big Conference Room Time” or “four monthly clock hours of Small Conference Room Time.” This was how Lou Reed’s Nephew spent his entire allotment.

The foam core sign he set up on an easel outside the room said simply, “PITCH YOUR IDEA.”

He explained all this to me one Tuesday after I had noticed his absence, only to find him alone in the Small Conference Room on my way to the bathroom. He sat so still the automatic lights \turned off, flickering on as I entered.

“And people do it? They come in and pitch ideas?”

“Usually a few.”

“They are looking for investors?”

“I’m sure.”

“And you are looking to invest?”

“Of course not,” he said.

“Do they know that?”

“Know what?”

“That you’re not looking to invest.”

“I have no idea. The sign says, ‘PITCH YOUR IDEA,’ so they do. Sometimes a line forms.”

“And?”

“Terrifically entertaining.”

“Can I join you?”

“I suppose,” he said. “I am wary of groups larger than two. Factions form and I always end up in the minority.”

Before he could elaborate, a baby-faced young man stuck his head in and asked with impossible enthusiasm, “Is this where I pitch my idea?”

“Yes,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. “Come in.”

I sat down in the chair next to Lou Reed’s Nephew so that we were at ten and two o-clock around the small circular table. We invited our visitor to sit down at six o’clock, reflecting the dynamics of the situation. It took him whole minutes to settle into the chair as he removed his hoodie and fumbled through his backpack for his laptop and hastily wrapped the cord of his headphones around them and stuffed them into his backpack like a child cramming clutter into a toy box. Everything about him seemed childish. His round cheeks still held baby fat, which bulged at his wrists, knuckles, and—if you looked carefully—at his middle. This was somewhat concealed by the fact that he was basically wearing pajamas, soft jersey pants that puckered at the ankles and a too small t-shirt that strained around his shmooishness. His hair was thin in both senses: There wasn’t much of it and what there was lacked vitality. He looked, in every aspect, like a gigantic baby, foreshadowing what was to come.

He took a deep breath, closed his eyes, and began.

“Do you know why baby names have gotten so strange?” he asked.

“Yes,” Lou Reed’s Nephew replied.

“I mean, how many ways can you spell Madison, right?”

“Right,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said.

“And who would want to spell it even one way?”

“Agreed.”

Lou Reed’s Nephew’s responses had no impact on the performance. Our guest was reading from a script with only one part.

“I do know why,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. I could see he relished derailing the pitch. “Would you like to know why?”

“… OK.”

“It’s simple math. No one wants to give their child the same name as someone they’ve slept with before their current partner. It leads to odd memories and uncomfortable discussions. And now that people in the industrialized world postpone settling down and have more sexual partners per capita before choosing a mate, the available names for each child born …”

“Slut shaming!”

“Excuse me. What is that?”

“I’m not sure,” the visitor blushed, realizing that calling out this infraction was not to his advantage. “But I believe you are doing it.”

“So,” Lou Reed’s Nephew continued. “The universe of available names for each child born has been reduced by the union of their parents’ sexual histories, so new names have had to be introduced.”

“That’s an interesting theory,” the visitor said, politely, suggesting he’d heard it before. I waited for him to share his own hypothesis.

“But the real reason,” he continued, “is an innate human instinct for SEO.”

“Humans have an innate instinct for search engine optimization?” I blurted. Lou Reed’s Nephew shot me a glance, reminding me I was there at his invitation.

“Why not?” he said. (If there were factions, he would be in the majority.) “If Chomsky can have his ‘Language Acquisition Device,’ no theory can be too overdetermined.”

“That’s why you get all these new spellings of Madison, for example,” our guest said, excited to have a defender. “Parents sense from ambient sampling that Madison, Maddison with a second ‘d,’ and even Madisyn with a “y” are becoming too competitive, so they move to the next available iteration.”

“Because more competitive names will be a handicap later in life,” I said, despite myself.

“Where does the ‘y’ go?” Lou Reed’s Nephew asked.

“Yes,” our visitor said, ignoring Lou Reed’s Nephew, just as the latter had feared. “This is the idea behind my new baby name algorithm, Beybi.”

He handed us his card so we could see the wordplay at work in the spelling. “Beybi: Authority for Life,” it read.

“Cute,” I said.

“It helps parents choose optimal names for future search volume,” he said. “‘Because you only get one shot at authority.’ That’s what we tell them. The parents.”

“Parents do love authority,” Lou Reed’s Nephew agreed.

After our guest left, Lou Reed’s Nephew asked for my feedback.

“I like the synergies,” I said. “You could promote this to all the Andreas who bring their Emilys in for texting lessons, maybe do a rev share?”

“That’s dried up. There was a Yelp incident.”

“And the insurance thing.”

“In any case,” Lou Reed’s Nephew continued, annoyed I was piling on his failure. “I like the thinking. Full lifecycle anxiety management. I suspected naming a child ‘Jane’ was shortsighted. Wish I’d had this in my back pocket. These pitches are so enlightening.”

“Just so I’m clear,” I said. “He plans to sell parents a service for which they already have an innate capacity?”

“We have to help nature along from time to time,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said.