Generation Trouble

The NYT sends me searching for mine.

Ten years ago we had some remodeling work done by a Czech contractor, which was the occasion for my most spectacular Curb Your Enthusiasm-grade gaffe to date.

As I texted my wife on his first day of work:

I just left Eastern Europeans in our apartment with a bunch of cash and some power tools.

Or at least I meant to text that to my wife, but texted it to the Czech contractor instead. There is simply no way back from this other than the Czech contractor having a great sense of humor, which fortunately he did. That evening, after an excruciating day of silence, he texted me a picture of our demolished bathroom, along with a note.

“Eastern European guys making good progress,” it read.

We spent a lot of time together over the next few weeks, like Eldin and Murphy Brown. It helped that I have a serious existential crush on Eastern European pessimism. In a sort of vulgar Hegelian anthropology, I feel like Eastern Europeans are the most wizened white people and white Americans are the most historically naive, as different from each other as possible while remaining in the same genus. Americans are cloyingly hopeful things will get better. Eastern Europeans are always certain they can get worse.

But I overgeneralize. My contractor exhibited a charming Czech exceptionalism. He was shocked and delighted that I owned a copy of The Good Soldier: Schweik. (And had read enough of it to bullshit about its absurd sendup of empire and war.) He was excited to tell me they had to break it into two movies in the Czech Republic. (Like Wicked, I guess.) He did have some reactionary leanings that liberals are always surprised to find in their immigrants.1 Russia had just invaded Ukraine and he saw it as an intra-Russian conflict, post-war sovereignty and the Prague Spring seemingly generating nationalism rather than empathy.

The second most comedic scene in our short relationship—I have already described the first—came when some technicians came to the apartment to fix the intercom. They were from the former Soviet republic of Georgia, and he vanished as soon as they arrived.

The Georgians spoke mainly to each other and were in the apartment for maybe forty-five minutes, during which time my Czech contractor made himself scarce in the bathroom. They were even physically different from him in a way one might find in Schweik. They were sullen, indistinguishable, and potatoish, like George Grosz drawings. He was quick and lean, a manic trickster.

After they left, he emerged and said to me in a conspiratorial whisper: “Russians!”

“I think they were from Georgia,” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “We call them Russians.”

“I was born in 1976, toward the end of the generation that includes individuals born between 1965 and 1980,” writes Amanda Fortini in the tablesetter for the latest attempt by the New York Times to make Gen X respectable, this time via T, its style magazine.

Yes, Amanda, we call them Millennials.

I know, I know. 1976 is well within all known demographic definitions of Generation X, so let me explain.

The thing about generational “theory”—the validity of which, as social science2, lies somewhere between scientific Marxism and astrology—is that it is both trivially true and absurd. True because obviously one’s position in history relative to one’s biological age has a large impact on one’s attitudes and consciousness. Absurd because the epochal dividing lines are entirely up for grabs. In other words, an infinite number of periodizations are possible, from the individual and useless—each a cohort of one—to the traditional Strauss & Howe borders, which define Generation X as those born between 1961 and 1981.

Those borders were first drawn in their book Generations, published in 1991, the same year as Douglas Coupland’s Generation X—too late, evidently, to palm the latter’s title. In this first formulation, what came to be known as Gen X was dubbed “13th Gen,” the thirteenth American generation in their scheme. The pair revisited (repackaged?) their system for the shorter and sexier The Fourth Turning—published with a different house in 1997—that now called the cohort to which I belong Generation X. This second book also forecast a cultural reckoning for right about … now, which earned it a following among change agents as diverse as Al Gore and Steven Bannon.

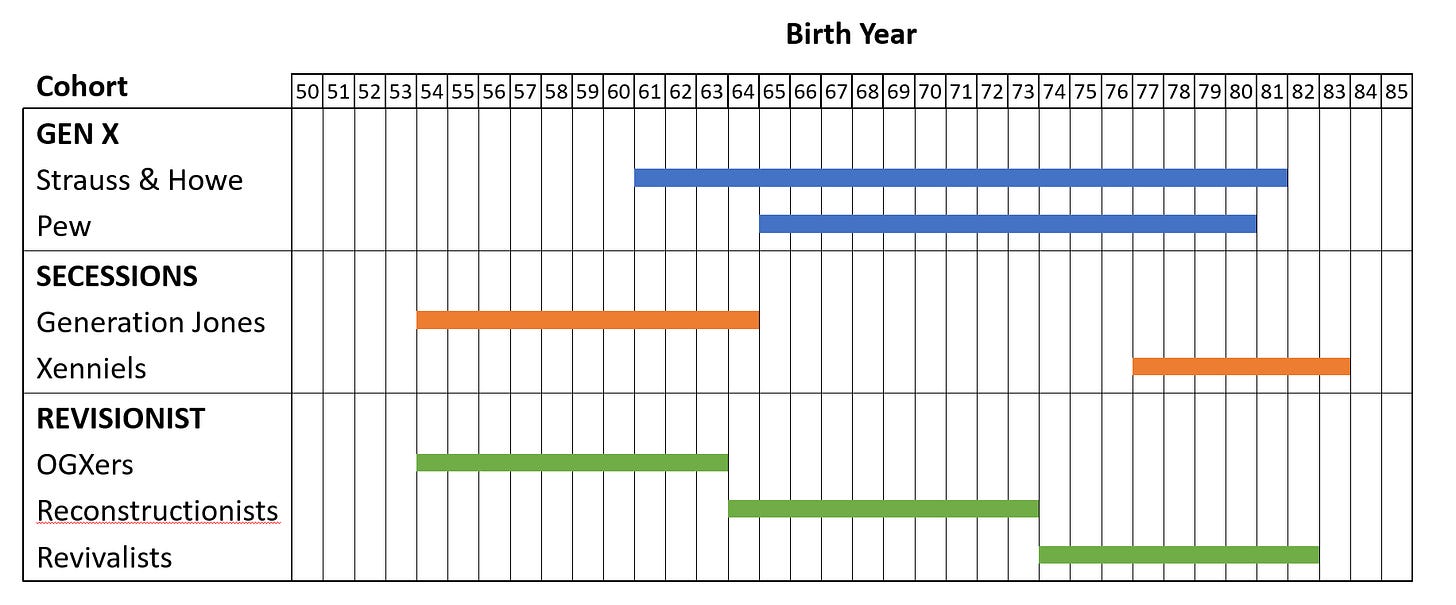

But, as I was saying, because time is—in fact—a continuum, where you draw the lines is fungible. In 1999, Jonathan Pontell carved out the second half of the Boomer generation as Generation Jones (those born between 1954 and 1965), and in 2014 Sarah Stankorb defined Xennials as those born between 1977 and 1983. Semiotician Joshua Glenn has been articulating an alternative periodization scheme that uses ten year cohorts since shortly after Generations first appeared, more about which later.

All such periodizations are equally defensible, reductive, and fascinating. If the opinion poll is the second lowest form of fake social science—the lowest being dating show “experiments”—generational periodization is one level up, the dilletante’s sweet spot. (I would know.) Some barriers to entry, but basic curiosity and a terminal masters will get you by. Plus the debates attract actual experts, slumming while avoiding dissertations on “the long Regency” or whatever.

In short, I can’t get enough of this stuff.

And what I would like to suggest is that any periodization that includes people who were out of college when grunge broke and those who were not, cannot possibly be right, because being a teenager in 1980s and the 1990s were two entirely different things, as different from each other as possible while remaining in the same genus, like me and my Czech contractor.

I was born on August 18, 1969. The day after Woodstock, cornily enough. (Though worlds away, on an Air Force base in Arizona.) Christian Slater. Ed Norton, and Masta Killa from from the Wu-Tang Clan were born on the same day. Matthew Perry was born the next day.

I think it is difficult for people under a certain age to understand how fantastically bad things looked for college graduates in 1991, though they will recognize the beats. War in Iraq, economic recession, no jobs, high housing costs. Reading Coupland’s Generation X today—I think I only read the marginalia when it came out—it is remarkable how much of it could simply be transcribed as the complaints of today’s twentysomethings.

The second chapter is called “Our Parents Had More” and there is a glossary entry for “Homeowner Envy,” which is defined as:

Feelings of jealousy generated in the young and the disenfranchised when facing gruesome housing statistics.

There is even an entry for “cringe,” which is called “squirming," defined as:

Discomfort inflicted on young people by old people who see no irony in their gestures.

This was thirty-five year ago. And (I can’t stress this enough) there was no hope. Reaganism had won in a rout. He carried forty-nine states in 1984—can you imagine?—and his blood boy successor George H. W. Bush’s approval rating was at 89% in a recession. I went to a public university that minted junior executives for nearby Procter & Gamble, and those people were worried about their futures, so a lot of us signed up to get advanced degrees in Pynchon, Foucault and Robert Burns. Because why not? The world was almost over.

But then, against all expectations, things changed. The apocalypse receded. Bush lost, grunge broke, Windows 95 kickstarted the dot-com boom, and Slacker was transmuted into Wired, where the people with advanced degrees in Pynchon, Foucault, and Robert Burns imagined that their aimlessness had been a genius move that well-positioned them for the dot-com boom. (If it had not, in fact, somehow magically brought it about.) If you hit the timing just right, you experienced this as pure generational effectiveness—like you had succeeded, where the Boomers had failed, in levitating the Pentagon.

The T Magazine package, which is cringily (squirmingly? ) titled “Is Gen X Actually the Greatest Generation” is entirely told from this triumphalist and—I would argue—fundamentally Millennial perspective. The author calibrates—as we all do— to an important year for her, 1994, the year she graduated from high school.

In 1994, Bill Clinton was president, the North American Free Trade Agreement had just taken effect and the figure skater Nancy Kerrigan was clubbed on the knee (an attack orchestrated by her rival Tonya Harding’s ex-husband) five weeks before the Winter Olympics. It was the year “Friends” and “ER” first aired, as did the lone season of the lovely but doomed “My So-Called Life.” “Natural Born Killers,” “Pulp Fiction,” “Ace Ventura: Pet Detective,” “The Mask,” “Dumb and Dumber” and “Legends of the Fall” were playing in theaters, and Kevin Smith’s “Clerks” — the black-and-white film about a pair of smartasses with dead-end jobs that would become a cult classic — debuted at Sundance. An astonishing number of consequential albums came out in 1994: Hole’s “Live Through This,” Nirvana’s “MTV Unplugged in New York,” Nas’s “Illmatic,” Liz Phair’s “Whip-Smart,” Tori Amos’s “Under the Pink,” Mary J. Blige’s “My Life,” R.E.M.’s “Monster,” Beck’s “Mellow Gold,” Pavement’s “Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain,” the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Ready to Die,” Oasis’s “Definitely Maybe,” Jeff Buckley’s “Grace” and on and on.

And all of these, almost without exception, appear to me as signs of past-peak decline and institutionalization. The road to Woodstock ’99, which no cohort wants to claim. In short, you either experienced Nirvana’s success as the beginning of something or the end of something, and that is the brightline between Xers and Xennials3. I mean, Liz Phair’s Whip-Smart?

I know I’m sounding all revolution-betrayed here, but that’s not it. There was no revolution to betray, but there was a specificity of experience and, perhaps, a trend that was slowed but not addressed.

I found it kind of surprising that, in his video interview, Coupland—while rightly claiming that he was essentially the first to say “Okay, Boomer”—goes easy on Millennials by saying that while Gen X was primarily concerned with “selling out,” they now have many other things to worry about. Fair, but selling out is no longer one of them, since selling out is now a given. Not because of some generational weakness, but because there is no longer anything outside commerce, thanks to the long-term effects of the dot-com boom that saved our bacon three decades ago.

Like the characters in Coupland’s novel, the first half of Gen X (to which I belong), was engaged in a sweet but doomed project: trying to stake out a sphere of independence from mass commercialization as the shadow of Sauron spread across the land. The project was naive and delusional—resulting in some self-defeating neuroticism—but it’s worth remembering. There was Fugazi and Ani DiFranco, who operated outside corporate economies. There were The Replacements, “the janitor, the drunk, and the child”—as one commentator put it—humping it from Duluth to Madison like some sort of myth. There were the unmainstreamable Dead Kennedys, who managed to figure out how to thumb their nose at liberals and Nazis at the same time. (It’s not as hard as you think, boys. Give it a shot.)

Other key cultural moments and figures for this leading half of Gen X—which are not mentioned in the T article—might include Robert Longo and Cindy Sherman, the Tipper Gore-run PMRC hearings (1985), the Mapplethorpe censorship controversy (1989), the Pixies (1986), the Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense (1984), and the movie Repo Man (1984).

I know what you’re going to say. A lot of these culture productions were not made by Gen Xers, but by trailing Boomers or Generation Jonesers. (’90s zinester Candi Strecker, in fact, suggested calling what amount to Jonesers the “Repo Man Generation,” long before Pontell appeared on the scene.) To this, I have no defense, other than to say that I’d prefer to caucus with them, rather than the Xennials currently taking a victory lap. A generation that captured teens of the ‘70s and ‘80s would make much more sense to me, or—at the very least—if Strauss & Howe’s initial designation is ceding territory on both sides, let’s have a name for what remains.

As it happens, Joshua Glenn’s scheme—which he began articulating in the pages of his ’zine Hermenaut almost as soon as Generations appeared—provides one. Here is a chart that shows the standard cohorts, the Gen X secessions, alongside Glenn’s revisionary scheme.

I’ve been aware of Glenn’s periodization since the ’90s, but I was surprised to find, while writing this, how clearly it anticipated the cusp secessions of Generation Jones and the Xennials and satisfies my requirement of having teens of the ’80s and ’90s treated separately.4

So I, like Glenn, am a Reconstructionist. He says this is one of the most popular post he’s ever published, perhaps as ’80s kids like me wander the Internet, looking for our lost souls. Here is his take on the cohort that lies between Generation Jones, which he calls OGXers, and Xennials, which he cals Revivialists.

Hazy sense of generational identity, splintery culture—and on top of that, when the 1964-73 cohort were undergrads, deconstructive theory was all the rage in humanities departments. Small wonder, then, that this cohort’s collective disposition is accommodationist—i.e., in the cognitive-development, not the political sense of that term. The 1964-73 cohort shares, that is to say, a marked tendency to brood over taken-for-granted cultural, political, social, and philosophical forms and norms, not rejecting but self-consciously remixing these fragments into innovative new patterns. In honor of the 1964-73 cohort’s post-deconstructionist capacity for accommodationism, I’ve named it (us) the Reconstructionist Generation.

He says, further, that this cohort “never developed generational consciousness,” which strikes me as a very Gen X—or, um, “Reconstructionist”—thing to say. I actually walked out of Reality Bites, in an attempt—I guess—to skirt categorization entirely. This always seems to happen: the final escape of the categorizer. Paul Fussell’s indispensable Class ends with a note about “Category X”—which is where Coupland says he got it—of people who opt out of the class system. People don’t buy books to feel boxed in, I suppose. Cohorts for thee, but not for me.

I agree with Glenn on the brooding, however. I think our cohort set ourselves a task almost as difficult and at least as self-punishing as rawdogging. We set out to be in the world while evading all its compromises, like Lloyd Dobler in Say Anything, The Graduate for this demographic. In the parallel to the “plastics” scene in the latter, John Cusack as Dobler is asked about his career plans. He responds.

I don’t want to sell anything, buy anything, or process anything as a career. I don’t want to sell anything bought or processed, or buy anything sold or processed, or process anything sold, bought, or processed, or repair anything sold, bought, or processed. You know, as a career, I don’t want to do that.

Even as he says it, he loses steam, realizing that what he wants is not achievable, just as Ben Braddock does on the bus when “The Sound of Silence” tinkles in once last time.

Say Anything was released in 1989. Two years later, war and grunge both broke out. Clinton won the next year, and in 1997 Strauss & Howe released the more popular revision of their original dry opus, formalizing the Generation X label. A decade later, we had been once more into Iraq and recession, and—now, once again—things look hopeless. Worse than 1991. Perhaps a miracle will occur, delaying the end once again, but if not, I pity Gen Z. Unlike Coupland’s characters, who banish themselves to the desert (Palm Springs) and take non-corporate jobs to live off the fumes of the ‘50s—they have nowhere else to go, and perhaps we never really did.

The same year that gave us The Fourth Turning, 1997, also produced the cultural document that I still think about as the apotheosis of my sub-cohort’s dilemma, a New York Times Magazine titled “The Ambivalent-About-Prime-Time-Players.” It’s about the generation of then-ascendant comedians that included Ben Stiller, Janeane Garofalo and David Cross, who made their names via The Ben Stiller Show, The Larry Sander Shows, and Mr. Show. (None of these shows rate a mention in the T Magazine package.) The description of their sensibility, gets it right, I think:

What they share is that they all began their careers determined to avoid the faceless, shticky punch-line stand-up that had dominated the cable-fed comedy boom. And having grown up with TV and come of age with MTV, they’re avid pop-culture consumers—snobs about what they like but often equally mesmerized by what they hate, and able to make fun of both in a way that’s likely to confuse anyone who’s not already a fan.

The article mentions, via a quote from Dana Gould, that what they all had in common, was a worship of cringe-comedy pioneer Albert Brooks.

In a devilish act of intra-generational treachery, the article’s author—David Handelman, who went on to write for several of Aaron Sorkin’s series—let Brooks himself have the last word. After a few thousand words of attempted aloofness by his spiritual children, Brooks gobbles them up like Chronos:

“To tell the truth,” Brooks adds, “I don’t think ‘selling out’ was ever very meaningful to 99.9 percent of the public. I think it’s an ego-based concept, that the world is thinking about you. If most of the world sees anybody on television, they’re impressed.”

Ultimately, Brooks’s advice to his comedy heirs is: ‘’If you want to keep working, you have to bend. But you don’t have to bend so much that you can’t live with yourself. Look, I’ve seen hard-core fans go through periods of my career where they went, ‘Aw gee, I wish you’d be this again or that again,’ but the fact is, where else are they going to go? I mean, sometimes my favorite restaurant has weird clams—where else am I going to go?’‘

Relax. Be yourself. Everything will work out.

What a Boomer.

In another context, with another Eastern European—a young Russian graphic designer named Boris—I had been naive enough to ask if he was happy his family had moved to the U.S. when he was a child. “Of course,” he said in the characteristic accent, like maybe I didn’t understand how the world worked.

Assuming such a thing is possible. See footnote 4.

Things that I would classify on either side of this line are snark and smarm, The Baffler and Wired, Gawker and N+1, Black Francis and Dave Grohl.

As it happens, Glenn and I are both in this cohort, which raises the specter of proximity bias that stalks this project, and likely all social science, where humans pretend to be able to regard themselves from above. In the docuseries Pretend It’s a City Fran Leibowitz addresses the potential folly in the face of generational opacity:

I believe that you can only really understand people that are your contemporaries. That you can’t really understand people who are not.

I profoundly understand some people my age. I mean just from looking at them. And when I say my age, I mean within ten years of my age either way. I know what their clothes mean. I know what they think their clothes mean. I know what they think they mean when they tell me what music they like or what books they like. But I don’t know this with people that are young.

!!!

Thank you for your takedown of the idea of a person born at the end of one random time frame being of a different "generation" from a person born at the beginning of the next. Continuum all the way! Also, your essays should be in a prominent, national publication.