The Quiet Part

What if saying it out loud is the trick?

Five years ago, I was in Seattle on business. The reports of COVID were mounting in the Northwest, and we had already agreed not to shake hands with our counterparts the next day. I was lying in my hotel room, hoping for a brief nap after the flight, when I heard shouts. I looked out the window and saw a parade of nurses marching for better wages, stopping traffic in both directions. Things are fraying, it occurred to me, seams are being stretched.

This was the final year of the first Trump administration. The system had been strained, and would be pushed to the edge by COVID and the summer of George Floyd. The Biden years followed, stable if uninspiring, the wheels rolled a quarter turn back from the brink.

Things do not announce when they are about to fall apart. Not as clearly as we would like. “Good guy with a gun” theorists imagine they could easily take out someone like James Holmes, who killed twelve people at an Aurora, Colorado, screening of The Dark Knight Rises in 2012. But that’s because Holmes is now who he became only shortly after the incident: a heavily armed maniac dressed like the Joker. But that isn’t how Holmeses appear in real time. There are no plot signals. No ominous music. No cinematic cues. There is noise, then confusion. Is this a joke? Is this real? Then it’s too late.

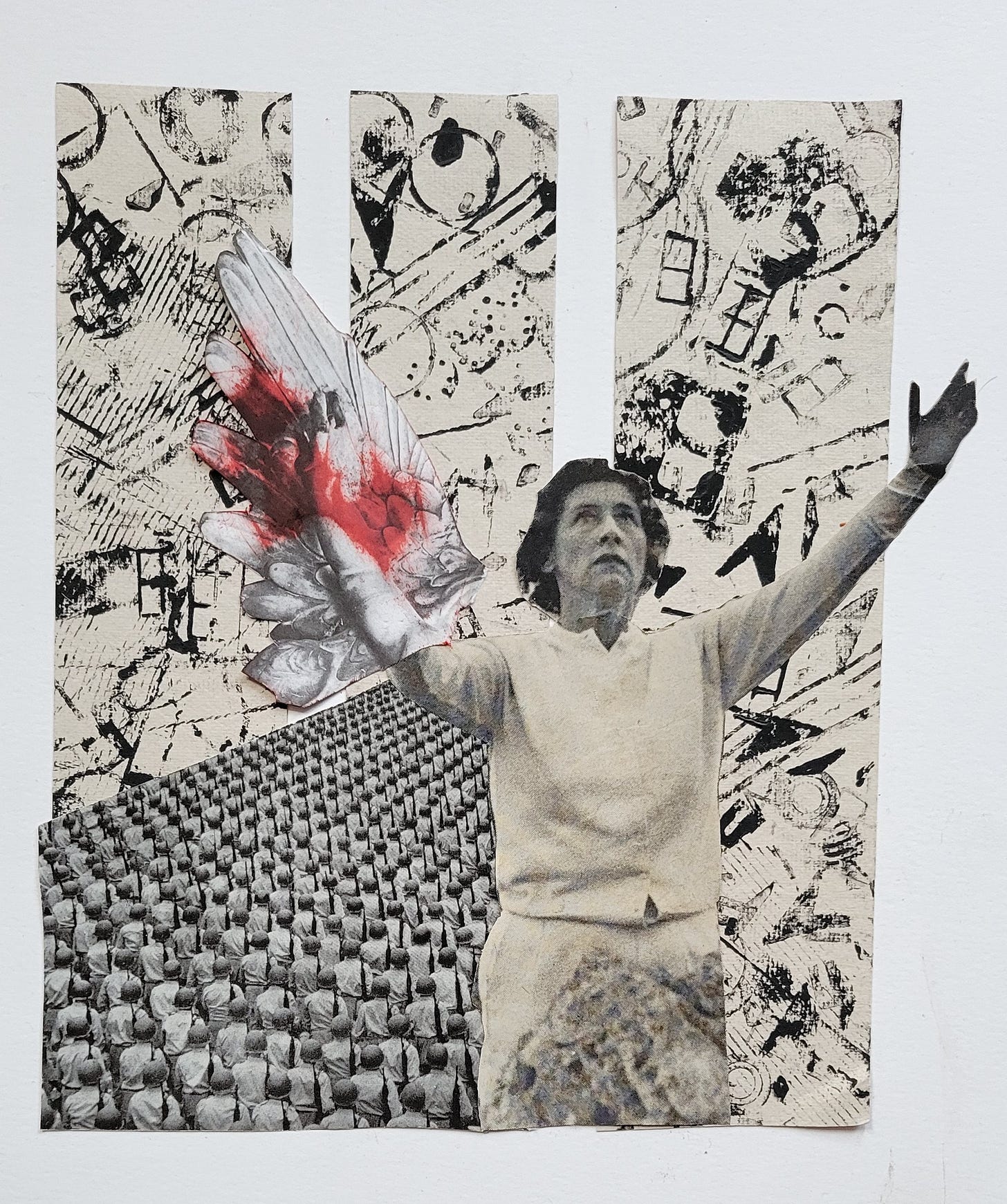

This fog of the now is well-captured in Alfonso Cuaron's depiction of the El Halconazo student massacre in Roma (2018). The event itself is seen peripherally—through a second story window and at a neck-straining angle—and is powerful precisely because it lacks clear framing and a comfortable focal point. There’s no slow-motion, no faces of noble suffering, no loved ones struggling to find each other in the crowd. There is just the sinking realization that things are falling apart, that chaos has won.

Cuaron is especially good at this sort of filmmaking, in which events emerge in the disordered way typical of real life. This is why the gun battles in Children of Men (2006) are more taxing than the call and response melees of action films or the numb battles between plot-armored standees in your average superhero blockbuster1.

The feeling I had that day in Seattle, however, brought to mind another piece of then-recent filmmaking: the BBC/HBO miniseries Years and Years, which had aired the year before. I have not met many people who’ve seen it, but those who have are a secret society of the shook, since the series succeeds in doing something quite frightening: showing, over the course of fifteen years, the UK drifting, slowly but surely, into fascism.

The fact that it does this so effectively is probably one of the reasons few people have seen it. Not because it is unpleasant or because some cultural hegemon condemns it to shadow, but because the truth of the story it tells cannot be told in a way that seizes the viewer by the lapels. It’s about how fascism arrives, not as Joker, but as James Holmes.

Written by Russell T. Davies, of Queer as Folk fame, the six-part series follows a family in Manchester as their lives become more precarious, braided with the story of the rise of Vivienne Rook (Emma Thompson) from foul-mouthed businesswoman to prime minister. Stephen’s (Rory Kinnear) downward trajectory is typical of the Lyons’ family fortunes. A financial advisor, he and his wife—a loan officer—are forced to sell their house in London when she loses her job to AI. The proceeds are then wiped out in a banking collapse, which triggers a recession, and the family is forced to move in with the family matriarch in Manchester. After making ends meet with courier jobs and by participating in medical experiments, he lands a job with an aspiring oligarch, which puts him in the room for the series’ most chilling scene.

The setting is Chequers, the summer house of the prime minister—now Viv Rook—and the occasion is an auction in which private firms are bidding to manage various “erstwhile sites,” places that used to be army bases or hospitals, but have since been converted into detention centers. Not only for refugees, it is clear, but for citizens as well.

As it dawns on Stephen what is elided by this term, “erstwhile sites,” Viv Rook swans in and interrupts:

Not everyone approves of the word “camps.” I'm sorry. “Facilities.” “Camps” have negative connotations. The “erstwhile sites” are being kept off the record in case people get upset, although personally I think the public are more stoic than that. As Victoria once said, “the British would only have a revolution if they change the laws on caravanning.”

Let's look at the words. Let's stare them down. The word “concentration” simply means a concentration of anything. You can fill a camp full of oranges it’d be a concentration camp, because of the oranges being concentrated, simple as that. (Oh, made it sound rather tasty.) The notion of a concentration camp goes way back to the 19th century, the Boer War. They were British inventions built in South Africa to house the men women and children made homeless by the conflict. Refugees, you see. Everything is much older than we think, and everything old happens again.

The scene is a master class in fascist rhetoric. There is a reference to stuffy, pearl-clutching pieties, then a compliment to the audience that they are more “stoic”—more realistic—than that, cauterized with a hot, jingoist dagger. Then the speaker gets real. She looks reality straight in the face. She says the quiet part—“concentration camps”—out loud, a vicarious thrill, before turning to defuse the word with banality and humor. Finally she appeals to tradition, ancient tradition—“much older than we think”—assuring those assembled that they are on a great, irresistible wheel that be can succumbed to without guilt and with more than a little bit of wisdom.

It’s like a horrifying magic trick, this scene. If James Holmes becomes the Joker—and the erstwhile sites of the 1930s became “concentration camps”—via the retrospective acknowledgment of terrible violence, this rhetoric demystifies and redomesticates these atrocities, decanting them back into everyday life, minus the warning tape and flashing red lights.

Like pretty much everyone my age, I was raised on Orwell’s essay “Politics and the English Language.” Its premise is that sloppy language enables sloppy thinking (on all sides of the political spectrum), which creates an environment in which the powers that be can launch a “defense of the indefensible” via jargon, vagueness, and a generalized fog of imprecision.

That is exactly not what is happening in this scene, however. In fact, Viv Rook interrupts a scene in which this is happening—in which concentration camps are being sanitized as “erstwhile sites”—to “say the quiet part out loud.”

The emergence of this trope, “X just said the quiet part out loud,” descends pretty much directly from the political faith in clear language espoused by Orwell and counter-signed by David Foster Wallace as late as 20012 (in his essay “Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage,” which includes a long footnote on the Orwell essay). The implication seems to be that now that the quiet part has been said out loud the game is over, the mask has fallen, and “the people”—having heard the unvarnished truth—will act accordingly.

According to this worldview, the people are confused, misled, uneducated, or uninformed. Once that is fixed, everything will work out. I was raised on this essentially Deweyan vision of liberalism, and its axioms have been my axioms my entire adult life3.

The realization that has been slowly dawning on me, and people like me—i.e. liberals—is that this theory of change is not now true, if it ever was4. What makes this scene in Year and Years so powerful and chilling (at least to liberals) is that it dramatizes the exact moment when that theory is proven to be false. Viv Rook is going “to say the quiet part out loud,” and people are going to love it. The greatest weapon in the liberal arsenal, “the truth bomb,” will be detonated and nothing will happen.

The malaise on the left following the 2024 election, it seems to me, was triggered by the shock of this non-incident. Liberalism put all its faith in a single weapon and it went off with a whimper.

The first reason this turned out to be the case is because of the rise of what has been called “behavioral politics,” which the right has embraced more readily than the left, for reasons consistent with their worldview. Given the insights of behavioral economics—which suggest that our decisions are informed by wildly irrelevant information to which we are contingently exposed—liberals have (at least officially) continued to address their audiences as coherent Jeffersonian subjects, advocating a coherent worldview that a rational person might be persuaded to adopt. At least since Bush II, on the other hand, the GOP has intuitively understood that reach and frequency are more important KPIs. And in that game, novelty is death. In a reconsideration of Orwell’s essay trenchantly titled “Teaching George Orwell in Karl Rove’s World,” Hans Ostrom and William Haltom observe as much.

What a political scientist or English professor may regard as banal [common] may still have an extraordinary effect. Within the spectacle, banal or commonplace language may produce uncommon results. The well known political “base” [speaking of banal terms] may be “energized” [as pundits say], not lulled, by banality. Therefore teachers of politics and English may need to be less presumptuous and smug about the deployment of banality. Indeed, those deploying the language may know well how banal the language is.

In other words, Orwell’s recommendation against dead language might be inimical to effective—if unlovely—political communication.

But something even more sinister than cant is being deployed by Viv Rook. Rook is not content with stultifying repetition, effective enough to elicit adequate response rates, but ultimately lacking in total energetic potential. To do that, nothing short of a resurrection is required. “Concentrations camps” cannot merely be laundered, they must be embraced. Aesthetically, this is why the scene is so powerful, which is to say titillating, albeit in a horrific register.

Although I have constantly read the philosophies of those who lived through the great contest for civilization that was the 1930s, the actual political facts of that time, until recently, remained abstract and fantastical to me. (And isn’t it strange that the most enduring English-language representation of the era is a musical?) We can’t quite get our heads around what happened. No one can. Gramsci. The Frankfurt School. Orwell. What spell had been cast with power or words or desire to make people choose such a thing as fascism?

Viv Rook is terrifying because she presents the idea that none of that was necessary. There is nothing terrifying about concentration camps, she argues, once you understand them correctly. We need only get over our “dictator phobia” as some suggest.5

Six years after Years and Year aired, it appears that we may have.

It is as felicitous as it was inevitable that the age of the superhero moving is coming to an end, if only because it was a straightjacket on aesthetic range of motion for both viewer and creator. “Canon” controls and eliminates the possibility of discovery and surprise. They are bedtime stories, with all that implies about their sophistication, which must never vary as we are told, again and again, the tall tale of how Peter Parker became a spider-man. There have been many attempts to solve this problem, and I appreciate most of them. M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable (2000) is the purest, made possible (I’m guessing) by the success of The Sixth Sense (1999), which enabled the director to make a superhero movie while persuading the studio not to market it that way, an experiment that can likely never be repeated. The Joker—as a character—has been the richest fodder for de-mythologizing, and I find Todd Phillips’ treatment satisfying, not least of all because it culminates by thumbing its nose at plot armor. Finally, one can pursue the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern strategy by adopting an in-world character about which the audience has little knowledge and few expectations and construct an authentic dramatic narrative, leveraging world mechanics, in what amounts to authorized fan fiction. This is the route taken by Andor, with satisfying results.

After Bush v. Gore but before the invasion of Iraq on clear, but false, premises. Louis Menand’s reconsideration of Orwell’s legacy in general—and “Politics and the English Language” in particular—appeared just a few months before the invasion.

Though it is clear now, as the only era I have ever known comes to an end, that this was a contingency of history. of post-war victory, prosperity, and the Cold War. Before World War II, Dewey was regularly clowned on for his naivete, by socialists and realists alike, with eyerolling retorts of the form, “John, the capitalists are not confused. They are just capitalists.”

I am inclined to think that it is true in periods of relative cohesion and consensus, but not true in periods of unraveling and transition, but that’s a discussion for another time.

Given how titillating/shocking (albeit in a horrific register) it is to hear Rook go for it and deliver a full-throated case for concentration camps, one can only imagine how titillating it must feel to certain young Americans to utter such heresies, the underestimation of which fact has lately come home to roost in various nihilisms that Dostoevsky would have easily recognized. In my day, such transgression boners were gotten from Fabrice Colette’s frank sexuality on the cover of The Smith’s Hatful of Hollow—not from samizdat Francoist memoirs—but those were different times.

Great work. Similar to your moment in Seattle, I recall that when the riots began after the Rodney King verdict I was genuinely puzzled as to how it was that everything went on as normal the next day. I think I felt like it was all truly broken now and we could not have business as usual until it was all addressed. Nothing was addressed.