The Undepressed Person

In memoriam.

The undepressed person had lately noticed a warm and persistent feeling growing, in the chest area—and also in the area below his eyes—that was difficult to acknowledge and even more difficult to describe, though its intrinsic incommunicability seemed helpless to undercut its (i.e., the feeling’s) essential joy.

This last word stuck in the undepressed person’s throat (figuratively, since he was not in fact trying to speak) as he lay on the couch one Sunday, listening to the unoiled swings frantically squeaking in the playground next to the apartment where he lived with his wife and realized that his depression was nowhere to be found. That this was even possible had only lately occurred to the undepressed person, who—for as long as he could remember—had considered depression such a part of himself, his family, and his generational cohort (viz., those born between 1965 and 1980) that he had never dared imagine that he might one day become undepressed.1

He had, he realized, kept this slow-rolling realization at bay for several months or perhaps years, not dealing with it, recognizing how disruptive it would be to his life and, frankly, how embarrassing it would be to discuss it with his friends and confidants, all of whom had become such based on a shared belief that life was one long shit-eating contest with no timeouts.

This collection of friends and confidants, what the undepressed person’s therapist called his (i.e., the undepressed person’s) Support System, had been collected in all the places where such people washup, like leaves against storm drains: bars, rehabs, graduate schools. With their help and support, he had carefully tended to this view of life like a dark garden, until it was a complete lifestyle, with its own assumptions, aesthetics, and jokes. Knowingly dark, inevitably sarcastic jokes.

As the undepressed person looked out the windows of his apartment at a sky that was irrepressibly blue2, poking at this realization, it occurred to him that the sky was “9/11 blue,” because that day had been so beautiful (as those who were there knew) but also because it had become a mental habit to pair things that were beautiful with things that were unspeakably tragic, just to, as it were, “take the edge off.”

He had been fully and completely depressed—with no hint of undepression on the horizon, despite ingesting 30mg of Paxil every morning going on two years—on that day. Walking east on 14th Street, the still-not-yet-undepressed person had seen a clump of people standing at Sixth Avenue, looking downtown, and remembered thinking, “What are these assholes looking at?”, his then-standard reaction to people anywhere doing anything.

When he reached them (i.e., the people), he looked where they were looking and saw the first tower smoking. A small plane had hit it, they said. This had happened to the Empire State Building before, he (i.e., the then-depressed person) remembered, so there was no immediate concern. Then, as they talked, the second plane hit from the south, blowing the north side of the building toward them, debris glittering like confetti. People started running toward the towers while the still-depressed person walked to Union Square and took the train to work, where he watched the towers fall on TV. He felt numb but—if he was honest—excited. Something was happening—an unscheduled timeout in the shit-eating contest of life—and he worried there was something very, very wrong with him.

This coprophagial view of life—that it was one long shit-eating contest, etc.—had been passed down to the undepressed person by his mother. Despite her small size and gregarious manner, she stored within herself an almost unlimited capacity for anger. When asked what her favorite movie was, for example, she did not say The Wizard of Oz or Gone with the Wind or any of the other problematic melodramas favored by women of her cohort (viz., those born between 1946 and 1964). She said Straw Dogs. Not the 2011 remake, which neither she nor the undepressed person had seen3, but the 1971 original directed by Sam Peckinpah, universally acknowledged as one of the most disturbingly violent films ever made.

The undepressed person explained this to his therapist, who was so old (viz., those born between 1928 and 1945) that he sometimes seemed to nod off during their sessions, and for whom—taken in the context of his long life, which encompassed a World War and the creation of Israel—Sam Peckinpah’s directorial career was barely a blip. In Straw Dogs (1971), the undepressed person explained, Dustin Hoffman plays a meek scientist who moves to a rustic English province where the villagers rape his wife and push him to and past his breaking point until, finally, he kills them all in progressively graphic ways. He (i.e., the undepressed person) then shared, also patiently (almost as if he worked for his therapist rather than the other way around), that it might seem surprising that this was the favorite movie of his tiny mother, who worked as a secretary at a pediatric dental office, but it was not if you knew her. She resented work, distrusted people, and believed (as the undepressed person had until recently) that life was one long shit-eating contest with no timeouts. But, and this was the interesting part (the undepressed person thought), his mother was very proud of how good she and her family (including the undepressed person) were at eating shit without complaining4. Her preference for Straw Dogs, however, instead of The Wizard of Oz, indicated to the undepressed person that perhaps there was a hidden cost to holding this view of life, a pent up and steadily mounting frustration that one might get a glance of in a person’s preference for ultra-violent ‘70s cinema.

The undepressed person’s therapist, once he had been jarred from his slumber by a clap of the undepressed person’s hands in the open space between them, agreed that the undepressed person might be onto something.

The undepressed person, as he lay on the couch, worried about how he would break the news of his phase change, as it were, to his Support System. Was it necessary to make a formal declaration, a coming out of sorts, in which he announced that he was open to views other than the view that life was a shit-eating contest with no timeouts? Or could he ease into it gracefully, on a conversation-by-conversation basis? For example, in his next Facebook chat with his friend who had stayed in graduate school and become a prominent Hegelian, when he (the friend) inevitably referred to what a slaughter bench history was, he (the undepressed person) might risk a palliative bromide, such as, “Did you notice today that the sun was shining, and that there was a crisp smell of salt in the air?”

The thought was terrifying.

The undepressed person could remember few antecedents of this warm and persistent joy-feeling he was now being forced to reckon with, and they had all occurred when he was on drugs. In his mid-20s, the undepressed person had friends, a couple, who lived in a warehouse above a muffler shop where a lot of people went to hangout. Artists and musicians, people who wanted to be artists and musicians, or people who were trying to figure out if they were artists and musicians before resigning themselves to life’s shit-eating contest with no timeouts.

They played poker Thursday nights in the unbelievable summer heat, which congealed during the week in the warehouse and would not entirely disperse even with the loading dock door flung wide open to catch occasional breezes off the river. Mostly they failed to play poker and succeeded in doing drugs. Weed. LSD and mushrooms. Occasionally a member of the group would get into crack or heroin, but they kept it to themselves or disappeared entirely. People who showed up to play poker quickly become frustrated since they had to keep telling everybody who’s turn it was to bet and keep people from dissecting indie rock song lyrics.

Then after things had gotten too boisterous to be contained—and people showed up who knew there was no poker and did not care—a dozen or so of the group would stumble together to a nearby bar, which never seemed to close. A two-story brick building with a claw-footed bathtub in one of the rooms upstairs, everyone said it used to be a brothel, though no one seemed to know when? Last century? Last week? It was impossible to tell. This hadn’t mattered to the undepressed person. All that mattered was that it was exotic and he could believe it was something quite different from himself. He was sick to death of himself.

They would buy quarts of beer on the first floor, then go upstairs and do drugs, the place all to themselves on Thursday nights since people in the neighborhood had jobs to go to.5 The undepressed person remembered one night that had lasted all the way to morning when the drugs were gliding into low terrain, coming in for a soft landing, and he looked out the second story window, past the vintage neon sight to a barren tree, its branches grasping like axons at the moonlight. His mouth was dry and cracking—the drugs had enabled him to drink thousands of beers, smoke millions of cigarettes—and he had opened his mouth and tried to form words, slowly, as if they were his first.

“Wh ...” he said.

“Why ...” he said.

“Why is the world?”

“Why is the world so ...?” he said before dropping his head into his arms, laughing hopelessly like a mental patient.

The two people who were still left up had been riveted by the undepressed person’s earnest delivery and both joined him in hysterical laughter when it had been mercifully cut short.

Back on the couch, this moment appeared to the undepressed person as pivotal. He suddenly felt the urge to call the one of these two people who was still living and complete the sentence he had cut short more than twenty years earlier in a reenactment that would be corny, yes, but also possibly “healing,” in a way the undepressed person was not yet ready to move out from behind quotation marks.

The living witness had been the ringleader and chief raconteur of their little group, one half of the couple who lived in the warehouse. He was the reason there was a group. He liked to talk, but he also liked to listen, and he made everyone in the group believe that they were surrounded by geniuses, that they were a group that mattered, like the Bloomsbury Group or the Fauves. He was also the one who spread the news if one of the group—the other, non-living witness for example—did not make it and died of drugs or suicide or natural causes, which was starting to happen, and he would always have praise for their talents, however unrealized they might have been.6

As he thought about this crucial event, a possibility dawned on the undepressed person that had not been there before, and this was that he had been wrong in believing that everyone agreed with his assessment of life and this belief had just been a function of his condition (i.e., his depression), to believe not only that life was unbearable but that everyone else believed that it was unbearable too, but that when he considered the living witness and his optimism then and his continued optimism now, maybe this wasn’t true at all, and that he had come within one sentence, all those years ago, of discovering that he was not alone, or rather that he was alone in his belief that life was one long shit-eating contest with no timeouts but that he could have been not alone with another idea entirely.

Before he knew it, he had dialed the number and the phone was ringing. The living witness answered. He sounded surprised but glad to hear from the undepressed person. He (i.e., the undepressed person) began to bring up the old times in the warehouse and in the bar that may or may have not been a brothel and the living witness agreed that these had indeed been fun and wild times and it was good they had (mostly) survived. He (i.e., the witness) did remember the night the undepressed person had begun to ask a seemingly profound question, only to stop, and how funny that had been, and he seemed to have no reaction, one way or another, when the undepressed person suggested he would now like to tell him (i.e., the witness) what he had almost said.

“Why is the world so beautiful?” the undepressed person said, after a long period of hesitation. Then he (i.e., the undepressed person) hung on, waiting for the silence to be broken.

The undepressed person being distinguished from the non-depressed person in that the former has been formerly depressed while the latter has never been, or never been seriously, while also noting that whenever the undepressed person had met seemingly non-depressed people in his life, particularly those of this generational cohort (viz., those born between 1965 and 1980), he had assumed that they were either lying or pathologically unaware of their surroundings.

The windows stared out at the street like two, sky-blue eyes, and reminded the undepressed person of the eyes of a particular author whose books he had always admired for their long, rambling accounts of life as one long shit-eating contest with no timeouts. He had seen this writer read a few times and had collected signed copies of his (the author’s) books dating all way the back to the one about failing to be an author and becoming a newspaper reporter who had sex with several women instead. What would he (the undepressed person) do with all his (the famous author’s) books now? He recalled that the famous author’s blue, blue eyes had put him on edge, as if they failed to entirely cloak a meanness and cruelty just on the other side.

Even without seeing it, the undepressed person felt confident it was both more graphically violent and less disturbing than the original, since—during his lifetime—this had been the overall trend in cinematic art. Events depicted had become simultaneously more “real” and less real, which had been the topic of a paper the undepressed person had written in graduate school before abandoning this career path for another career path, which he then abandoned, and so on, as he stumbled (albeit successfully, buoyed by certain privileges but also driven relentlessly forward by an unquenchable thirst for approval) from one vocation to another.

Complaining about the shit they themselves were meant to eat, that is. The undepressed person’s mother was forever complaining about the complaining others did about the shit they were supposed to eat, as if these people (e.g., the others) were completely and totally ignorant of that fact that life was a shit-eating content with no timeouts and a comprehensive ban on complaining.

The very existence of the people in the neighborhood—who were of a different race than the undepressed person—heightened the experience, even in their absence. And sometimes the undepressed person and his friends did go to the bar on Fridays and Saturdays, when they were the minority and the music was completely different and the undepressed person painfully remembered being called out by his friend, the future prominent Hegelian, for adopting what would now be called a “blaccent,” which the undepressed person totally acknowledged doing out of a compulsive need to evacuate himself entirely and to inhabit/invade the world of people more authentic himself, which acknowledgement nevertheless did not head off a drunken sidewalk shouting match between the undepressed person and the future prominent Hegelian on the topic of colonialism.

Some of the undepressed person’s generational cohort (viz., those born between 1965 and 1980) had not made it to the last third of life, but how many had surprised him, given that he himself had not planned to live past twenty-eight and, finding himself nearing twenty-nine, had seen no other choice but to stop taking drugs and face the shit-eating contest full on, with no buffers, until slowly he realized that life was something he’d rather have than not, so he stopped smoking cigarettes, etc. until he emerged, one Sunday on his couch, undepressed. This made it all the more sad, however, that some of his cohort and not made it—many of these among the most talented*—and while he knew that the socially sanctioned response to this was to bemoan the state of mental health and addiction treatment, the undepressed person could not help but think that this survival thing had always been a game of inches and that while he had ended up an inch to one side, others—both close to him and some only known to him—had landed just more than an inch in the other direction, which made the undepressed person realize that entertaining even a millisecond of depression for the sake of aesthetics or jokes was disrespectful to those people and perhaps even morally repugnant, bordering on sin, if there could still be such a thing in a disenchanted world.

*E.g., the one who wrote “Advice to the Graduate" and the one who sang “All My Little Words” and the one who wrote “The Depressed Person,” a short story that appeared in the January 1998 issue of Harper’s, half the undepressed person’s life ago.

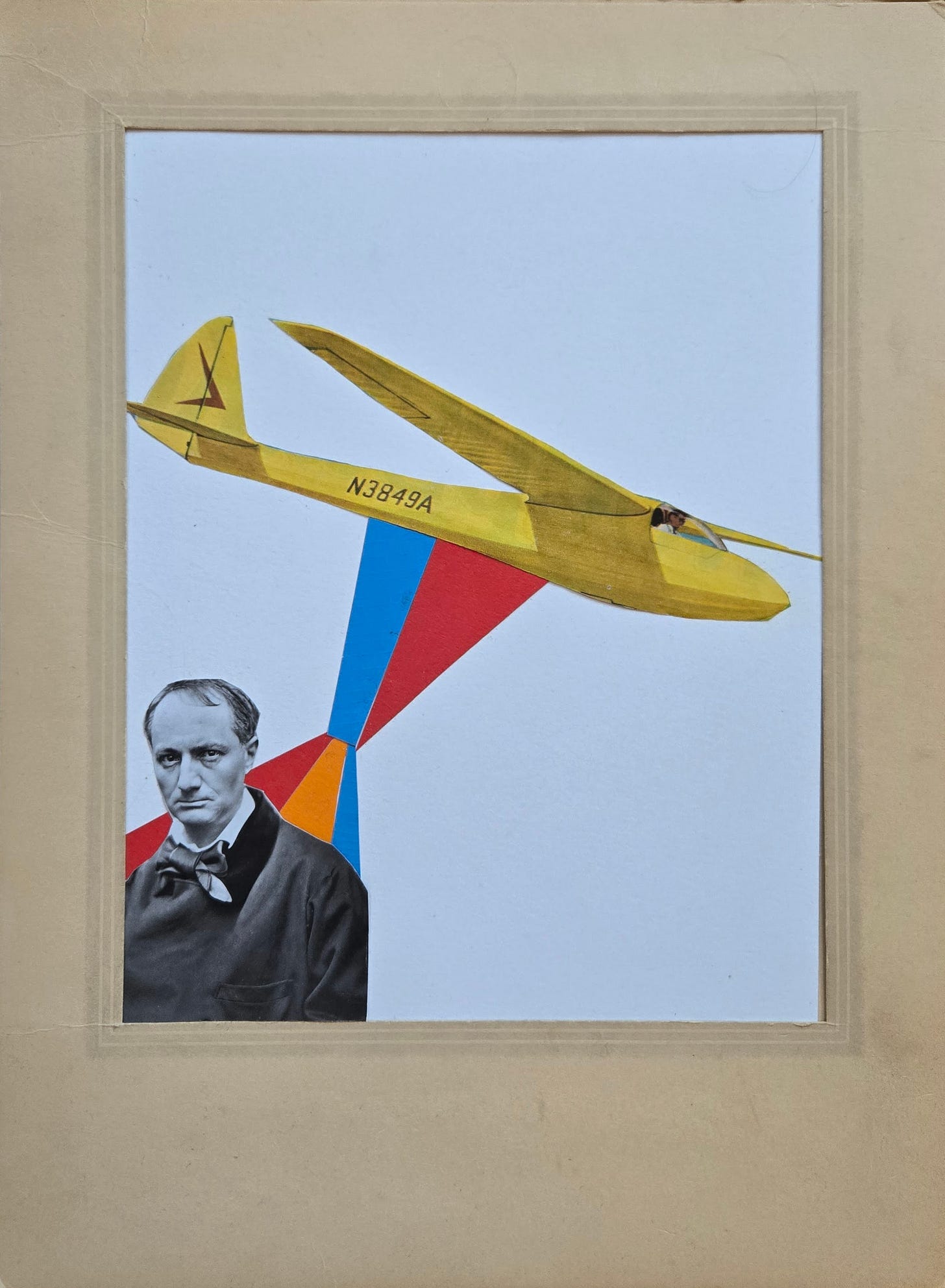

Amazing. I could read 1,000,000 words of this prose. Also the collages - damn. PS: I had a very similar “why?” experience while tripping with friends. They were aggravated at the time…. because I kept asking, apparently.